Iran Crypto Import Risk Calculator

- CBI Licensing Required

- AML/KYC Documentation Needed

- KYC/AML Reports Must Be Submitted

- Transaction Delays Possible

- Western Bank Restrictions Apply

Enter transaction details and click Calculate to see risk level

- Volatility: Bitcoin price fluctuations can affect profit margins.

- Regulatory Bottlenecks: Approval delays add complexity to logistics.

- AML/KYC Scrutiny: Western financial institutions monitor such transactions closely.

- Energy Risks: Use of subsidized energy may attract ESG concerns.

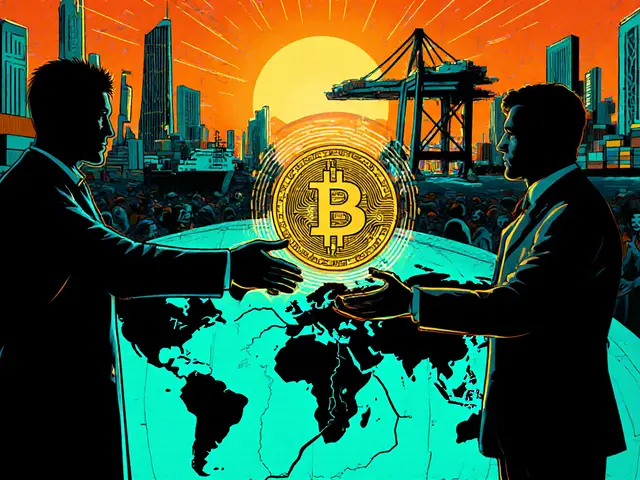

When you hear about Bitcoin is a decentralized digital currency that lets users move value across borders without a bank. It’s the engine behind Iran’s new way to import goods while its economy sits under heavy sanctions. The Islamic Republic has turned a once‑illegal hobby into a state‑backed tool for trade, but the system is anything but simple. Below is a step‑by‑step look at how the regime makes Bitcoin imports Iran work, which agencies hold the reins, and what the biggest hurdles are for anyone trying to do business with Tehran.

Why Bitcoin Became Iran’s Sanctions Workhorse

Sanctions cut off traditional dollar‑based channels, leaving Iranian importers with a glaring financing gap. Bitcoin offers three distinct advantages that the regime exploits:

- Borderless settlement - No SWIFT code or correspondent bank is needed.

- Pseudonymous transactions - While not fully anonymous, the public ledger makes it harder for regulators to trace the origin of each coin.

- Programmable contracts - Smart contracts can lock funds until delivery conditions are met, mirroring escrow.

By turning mined coins into a quasi‑currency for trade, Iran sidesteps the U.S. dollar’s dominance and reduces exposure to seizure.

Iran’s Dual Crypto Regulatory Framework

The system rests on two seemingly contradictory rules:

- The Central Bank of Iran (CBI) acts as the sole authority that can approve cryptocurrency exports and imports for trade settlement. It strictly bans any domestic crypto payments for consumer goods.

- At the same time, the government encourages large‑scale mining, granting industrial electricity tariffs to licensed farms. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) has become a key player in owning and operating those farms.

This duality creates a controlled pipeline: miners sell Bitcoin to the CBI, the bank converts it into a settlement token for approved import contracts, and the cash‑flow returns to the miner as revenue.

Licensing, Mining, and Export Process

Every step is overseen by a different agency, which means businesses must navigate a maze of paperwork. The table below captures the core actors and their responsibilities.

| Agency / Entity | Primary Role | Key Requirement for Traders |

|---|---|---|

| Central Bank of Iran (CBI) | Authorizes all crypto export transactions and holds the settlement ledger. | Obtain a CBI‑issued crypto‑trade license and submit KYC/AML reports for each shipment. |

| Ministry of Industry | Approves import of mining hardware and allocates industrial electricity quotas. | Register mining equipment with the ministry before any hardware purchase. |

| IRGC‑Linked Mining Farms | Produce Bitcoin at scale; sell the output to the CBI under contract. | Ensure the buyer’s wallet address is whitelisted by the CBI. |

| Iran Cyber Police (FATA) | Enforces AML/KYC compliance and monitors illegal mining activity. | Maintain real‑time transaction logs accessible to FATA auditors. |

Because every outbound crypto flow must pass through the CBI, payments often take 2-4 business days, longer than a typical wire. The extra delay is the price of staying on the legal side of the regime’s sanctions‑evasion safeguards.

Real‑World Trade Examples

The first publicly documented crypto import occurred on 9August2023, when Iran bought $10million worth of an unspecified digital asset to settle a steel purchase from a Russian supplier. Since then, the volume has exploded:

- By the end of 2024, $4.18billion in crypto left Iran, a 70% jump from the previous year.

- Between 2018 and 2024, Iranian firms processed roughly $8billion through Binance to bypass U.S. restrictions.

- In 2022, a 175‑MW mining farm in Rafsanjan (Kerman province) - jointly run by an IRGC‑linked entity and Chinese investors - generated enough Bitcoin to cover around $1billion in import bills.

These numbers show that Bitcoin isn’t a fringe experiment; it’s a mainstay of Tehran’s import strategy, especially for high‑value commodities like oil‑refining equipment, pharmaceuticals, and automotive parts.

Energy Consumption and Grid Strain

Large‑scale mining is power‑hungry. An ASIC miner can draw 3kW continuously; a 1‑MW farm needs roughly 8500kWh per day. Iran’s electricity tariffs for licensed farms are heavily subsidized - sometimes effectively free - which has drawn criticism from the Ministry of Energy.

Power outages have become frequent in residential zones, and investigations point to the “crypto cartel” of IRGC‑linked farms as a hidden drain on the grid. The government’s response has been mixed: on one hand, it cracked down on illegal household‑level miners in 2021; on the other, it continues to grant industrial‑scale farms preferential access to cheap energy because of the foreign‑exchange earnings they generate.

Risks and Compliance Tips for International Traders

If you’re considering a deal with an Iranian counterpart, keep these practical points in mind:

- Volatility - Bitcoin price swings can erode margins. Use stable‑coin bridges (e.g., USDT) where permitted, but remember they still fall under CBI oversight.

- Regulatory bottlenecks - The CBI’s approval queue can add days to settlement. Build a buffer into delivery timelines.

- AML/KYC scrutiny - Western banks will flag any crypto‑linked transaction with Iran. Prepare comprehensive source‑of‑funds documentation and be ready for heightened due‑diligence requests.

- Energy‑related reputational risk - Partnering with farms that use subsidized electricity may attract ESG criticism. Ask for proof of clean‑energy sourcing or carbon offset certificates.

In short, treat a Bitcoin‑enabled import as a multi‑layered contract: (1) the crypto purchase, (2) the CBI settlement, and (3) the physical goods delivery. Each layer has its own legal and operational risk profile.

Future Outlook: Will the Model Survive?

Analysts project Iran’s crypto sector will hit $1.9billion in revenue by the end of 2025, growing at a 23.7% annual rate. However, sustainability hinges on three factors:

- Energy policy - If the government decides to curtail subsidies or impose stricter caps on industrial consumption, mining output could fall sharply, reducing the pool of Bitcoin available for trade.

- International pressure - New U.S. or EU sanctions targeting crypto‑related entities (especially the IRGC) could force the CBI to tighten its licensing regime, making approvals harder to obtain.

- Technical evolution - The rise of proof‑of‑stake networks could diminish Bitcoin’s dominance as a trade token, pushing Iran to explore alternatives like Ethereum’s layer‑2 solutions or state‑backed digital currencies.

For now, Bitcoin remains Iran’s most viable bridge across the sanctions wall. The system is messy, but it delivers a clear benefit: converting domestically generated energy into a tradable asset that can bypass the traditional banking system.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does the Central Bank of Iran actually approve a Bitcoin transaction?

The CBI requires the exporter to register a crypto‑trade license, submit the wallet address of the buyer, and provide a detailed invoice. Once the paperwork is reviewed (usually within 48‑72hours), the bank records the transaction on a private ledger that mirrors the public Bitcoin blockchain, then authorizes the release of funds to the seller.

Can I use stablecoins instead of Bitcoin for Iranian imports?

Stablecoins are technically allowed, but the CBI only recognizes a narrow list of assets for official settlement. Most traders convert Bitcoin to a stablecoin off‑chain after the CBI clears the transaction, then use that stablecoin for the final payment to the supplier.

What are the biggest compliance red flags for Western banks?

Any link to the IRGC, unexplained cash flows exceeding $100,000, and the use of anonymizing mixers or tumblers. Banks also watch for rapid conversion of Bitcoin to fiat within 24hours, which suggests evasion of sanctions.

Is the electricity subsidy for mining legal under Iranian law?

Yes. The Ministry of Industry classifies licensed mining farms as industrial users, granting them reduced tariffs. However, illegal household‑level mining is prohibited and subject to fines or confiscation.

What happens if a Bitcoin transaction is rejected by the CBI?

The funds remain locked in the seller’s wallet, and the CBI issues a compliance notice detailing the missing documentation. The parties must resubmit the correct paperwork before the transaction can be retried.

Brooklyn O'Neill

December 13, 2024 AT 14:37It's fascinating to see how Bitcoin can become a lifeline for people facing heavy sanctions. The flexibility of crypto offers alternatives that traditional finance simply can't match. I think this could inspire other regions under similar pressure to explore digital assets.

Patrick MANCLIÈRE

December 16, 2024 AT 12:04Exactly, the decentralized nature sidesteps many of the geopolitical roadblocks that conventional banks hit. Plus, the ability to convert to stablecoins reduces exposure to Bitcoin's notorious volatility during transaction settlement. It's a clever workaround that showcases crypto's real‑world utility.

Ciaran Byrne

December 19, 2024 AT 09:30Bitcoin offers anonymity and speed, which are crucial under sanctions.

Carthach Ó Maonaigh

December 22, 2024 AT 06:57Sure, but let’s not forget the price swings can turn a sweet deal into a nightmare faster than you can say "blockchain". Those folks need to be ready for the rollercoaster.

Marie-Pier Horth

December 25, 2024 AT 04:24One might argue that Bitcoin, like a modern Prometheus, brings fire to the shadows of oppression, yet it also casts long, flickering doubts about ethics and sustainability. The dance between freedom and chaos is ever‑present.

Gregg Woodhouse

December 28, 2024 AT 01:50Crypto can help.

F Yong

December 30, 2024 AT 23:17Well, isn’t it just charming how governments scramble when a decentralized ledger steps onto their stage? It’s almost poetic, if you enjoy watching bureaucratic ballet.

Sara Jane Breault

January 2, 2025 AT 20:44People really need to stay aware of the AML/KYC rules they might face.

Keeping proper docs can smooth the process a lot.

Enya Van der most

January 5, 2025 AT 18:10Yo, the energy side is wild! Mining on subsidized power can make the costs crazy low, but you also risk drawing ESG heat. Still, the sheer hustle in those farms is something to admire.

Eugene Myazin

January 8, 2025 AT 15:37Totally agree, the cultural exchange that crypto enables is a game‑changer. When we look at the global picture, these cross‑border transactions open doors that were previously sealed shut. It’s not just about evading sanctions; it’s about creating new economic pathways.

karsten wall

January 11, 2025 AT 13:04The jargon around risk scoring can be a bit dense, but breaking it down: volatility, transaction size, and energy source all feed into the overall risk matrix. Understanding these variables helps stakeholders make informed decisions rather than guessing.

C Brown

January 14, 2025 AT 10:30Ha! Let them quake over a few extra points in a risk score. The real battle is who gets to write the rules, and they’ll keep tweaking the model while we just try to move goods.

Noel Lees

January 17, 2025 AT 07:57Honestly, the whole thing feels like a high‑stakes poker game, and every emoji I drop is a tiny reminder that we’re all just trying to stay afloat. 😅

Raphael Tomasetti

January 20, 2025 AT 05:24From a compliance angle, keeping transaction values under the million‑dollar threshold can reduce the risk tier noticeably. It’s a practical tip that many overlook.

Jenny Simpson

January 23, 2025 AT 02:50Sure, the mainstream media loves to paint Bitcoin as a villain, but the reality is far more nuanced-a double‑edged sword that can both empower and destabilize depending on who wields it.

Sabrina Qureshi

January 26, 2025 AT 00:17Wow!!! This is absolutely mind‑blowing!!! The layers of complexity are just astonishing!!!

Rahul Dixit

January 28, 2025 AT 21:44Is anyone really surprised that sanctions push countries toward crypto? It's the classic “when the going gets tough, the tough get blockchain.”

CJ Williams

January 31, 2025 AT 19:10Great points! 😊 Staying updated on regulatory changes is key, and using emojis can lighten the heavy topics. Also, watch out for typos-they can cause misunderstandings! 😉

mukund gakhreja

February 3, 2025 AT 16:37Honestly, it’s a bit laughable how quickly the narrative flips when a new tech disrupts the status quo, but that’s the nature of progress.

Ron Hunsberger

February 6, 2025 AT 14:04Bitcoin’s role in Iran’s import ecosystem under sanctions is a multi‑faceted phenomenon that warrants an in‑depth look. First, the decentralized ledger provides a channel that bypasses traditional SWIFT restrictions, which are heavily monitored by Western banks. Second, the volatility of Bitcoin, while a risk, can be hedged through stablecoins such as USDT or USDC, offering a more predictable value during the transaction lifecycle. Third, regulatory compliance within Iran still necessitates adherence to the Central Bank of Iran’s licensing regime, meaning that entities must secure appropriate permits before moving crypto‑based funds. Fourth, the energy aspect cannot be ignored; much of the mining power is sourced from subsidized electricity, often tied to the IRGC, which raises concerns about sanction evasion and ESG implications. Fifth, the AML/KYC documentation required by Iranian authorities mirrors international standards, compelling businesses to maintain rigorous reporting structures. Sixth, transaction size plays a pivotal role, as larger transfers attract heightened scrutiny and possible delays, especially when exceeding the $1 million threshold. Seventh, the use of crypto wallets with built-in privacy features can obscure transaction trails, thereby complicating enforcement actions by sanctioning bodies. Eighth, partnerships with foreign crypto exchanges that are willing to operate within this grey area provide necessary liquidity, but also introduce counter‑party risks that must be carefully managed. Ninth, the adoption of hardware security modules (HSM) and multi‑signature wallets adds an extra layer of security, ensuring that private keys are not compromised during cross‑border movements. Tenth, the legal landscape is in flux; recent U.S. Treasury statements have hinted at broader enforcement, meaning that compliance strategies must be adaptable. Eleventh, economic incentives for local merchants to accept Bitcoin payments have grown, creating a de‑facto parallel economy that operates semi‑independently of the formal banking sector. Twelfth, the psychological impact on consumers-seeing a tangible alternative to fiat-fosters a sense of financial empowerment amid hardship. Thirteenth, from a macro perspective, the increased crypto activity could gradually erode the effectiveness of sanctions, prompting policymakers to rethink traditional tools of economic coercion. Fourteenth, education and awareness campaigns are essential to mitigate risks associated with scams and inexperienced users entering the market. Finally, while Bitcoin offers a viable conduit for imports under sanctions, it is not a panacea; the blend of technical, regulatory, and geopolitical factors creates a complex tapestry that each stakeholder must navigate with diligence.

Kamva Ndamase

February 9, 2025 AT 11:30You gotta love the sheer audacity of using crypto to keep commerce alive! It’s like watching a high‑octane race where the drivers are dodging sanctions at every turn. The energy‑hungry miners powering these transactions are a double‑edged sword-cheaper power for them, but also a spotlight for ESG watchdogs.

Janelle Hansford

February 12, 2025 AT 08:57Exactly, staying positive and sharing knowledge helps the whole community thrive. And when we keep the conversation lively, more people can learn how to navigate these tricky waters.

Marie Salcedo

February 15, 2025 AT 06:24Bitcoin can be a real lifeline when traditional banks are blocked. Simple steps and clear guides make it easier for anyone to get started.

Mangal Chauhan

February 18, 2025 AT 03:50From a formal standpoint, it is essential to document each transaction meticulously. 📄 This ensures compliance with both local and international regulations. Moreover, employing a structured approach helps mitigate the risk of inadvertent breaches.

Darius Needham

February 21, 2025 AT 01:17Interesting how the crypto space keeps evolving to address these geopolitical challenges. It shows the adaptability of technology when people need it most.

carol williams

February 23, 2025 AT 22:44Let’s be honest, the drama surrounding sanctions and crypto is like a never‑ending reality show. Everyone wants the spotlight, but few understand the backstage mechanics.

Maggie Ruland

February 26, 2025 AT 20:10Sure, crypto’s hype is real, but the actual utility under sanctions is where the rubber meets the road.

jit salcedo

March 1, 2025 AT 17:37One could argue that the whole system is a grand illusion, a digital mirage designed to distract from deeper power structures. Yet, the grassroots adoption tells a different story-people are finding real value.

Lisa Strauss

March 4, 2025 AT 14:37Staying optimistic is key; sharing resources and support keeps the community resilient.